Ballpark Blues

At a Strip of Gay Clubs in Southeast, One Last Inning Before Striking Out

By Hank Stuever

Washington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, April 4, 2006; Page C01

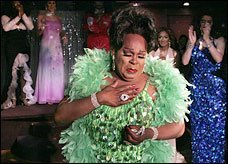

No amount of Whitney Houston and Toni Braxton and Mariah Carey songs could mask the pain. One by one, until the wee hours Monday morning, the reigning drag queens of Half Street SE descended the stairs at Ziegfeld's cabaret to strut their last, blowing kisses to admirers and making a few more sweepingly glamorous gestures -- all of it a farewell to the shabby but perfect place they called home for three decades.

Ziegfeld's, and four other establishments on the same forsaken industrial block at Half and O streets, closed yesterday in a cruelly predictable high school metaphor: The jocks win.

The city's oldest stretch of gay-oriented clubs, which date back to the 1970s, just happen to sit smack in the footprint of the planned Nationals baseball stadium. There were two years of rumors about closing or moving. Certainties were followed by brief reprieves, while the city argued with Major League Baseball on the stadium deal. Word came last week from a judge that the buildings have to go, so construction can begin.

Ella Fitzgerald (nee Donnell Robinson), the drag performer who ruled the roost here since 1980, dabbed at her eyes all night and complained of hip problems, wondering if the world would see her next on crutches, or in a wheelchair. She lip-synched to Donna Summer's "Last Dance." Then, in keeping with particularly moving drag performances, she gave the DJ the signal and did the song again. (People wept twice.)

All these years, Ella "has waddled up and down this dance floor. You can see the path she's worn," another drag queen, Xavier Onassis Bloomingdale, told the packed-sardine crowd -- gay men, mostly, and not all of them the kind you see on HGTV. Far from the happy, let's-walk-the-Labrador-to-Whole-Foods realm of Logan and Dupont circles, the O Street scene was the real deal: grubby, hidden even within sight of the Capitol, and just plain ugly-gorgeous.

Xavier, a wicked-eyed diva who has performed at the club for a fraction of the time Ella has, trash-talked the crowd into a mild frenzy: "Now they're going to build a baseball stadium here. And what are we going to do when it's done? Burn it down! That's right! We are gonna burn! It! Down! . . . [Bleep] baseball! Who gives a [bleep] about baseball?"

So now you've done it, Washington. You've spurned the queens, and they are both heartbroken and livid. Besides Ziegfeld's and its full-frontal go-go annex, Secrets, the block was also the home to the Glorious Health Club, Follies (a "movie theater," in the language of old newspaper clippings, back when police were raiding the place, charging the, um, moviegoers with acts of sodomy), and another club called Heat. Nation, a nightclub a few blocks north, has announced that it's closing July 16 to make way for an office building.

The buildings at Half and O were owned by Robert Siegel, who is still in mediation with the city over the financial compensation he and the business operators will receive, and whether they relocate.

Ziegfeld's and Secrets are owned by Allen Carroll and Chris Jansen, who have promised their clientele (in ads in the gay press, and in person at the farewell bash) that they are going to reopen -- someday, somewhere.

But no neighborhood wants them, and saving the clubs has so far not been placed very high on the gay agenda. Early in the baseball debate, after a proposal to relocate some clubs in Ward 5 was met with complaints, the city attempted to find Ziegfeld's another option:

"In P.G. County," scoffed Carroll, who told a city representative, "I am born and raised in D.C., and I have been down here 31 years. And they want us to move to Prince George's County?"

On the final night he was at his usual spot at the end of the bar, counting and stacking moist currency. Ziegfeld's economy revolved around dollar bills, which the bartenders -- always older guys in tuxedo shirts and bow ties -- would routinely give as change, so you would bestow them on your favorite drag queen, who would clinch heaps of cash in each fist like a pair of bridal bouquets.

It's too noisy in here to talk, Carroll said, and pulled us into a small closet filled floor-to-ceiling with liquor. Whatever inventory isn't consumed tonight, he said, will be held by the alcohol and beverage commission while the club looks for a new home.

He opened a package of mints. "I feel awful," he said of the closing. "Just all the memories, all the people. They always come back. People I haven't seen for years, somehow they always find a way back down here. I should put it all in a book -- no names, though."

A lot of it actually has all been recorded, in the written histories of gay culture in Washington. Driven by an unfriendly police chief in the '70s down to the blight of the Navy Yard, the seamier clubs thrived here. It became the opposite of more mainstream, ho-hum homo club life. Going down to Navy Yard made you feel a little dirty (or a lot dirty), in an adventurous or perhaps even anonymous way. It never felt completely safe. Parking was plentiful but dicey. Razor wire and cinder blocks -- it was a look, and it is perhaps irreplaceable. It may be hard to understand Half and O as a lost gay authenticity; harder still to assign it any civic value.

So come back inside Ziegfeld's. Understand it, at the very least, as home.

It was not a big club. The carpet was threadbare. There was a small stage, and a stair leading up to the holiest sanctum -- the performers' dressing room. There was a retractable disco ball over the scuffed-up dance floor, and a lethargic smoke-belcher for occasional effects. The cocktail waiters were shirtless. The walls were garishly lavender. There was a big U-shaped bar in the back, and a door leading into Secrets and all that it might hold.

A drag-queen customer in a purple velvet dress and "Hart to Hart" hairdo, who goes by the name Stephanie Bunns and stands 6 feet 8 in her platform sandals, ordered another in a string of White Russians and said she had no idea where she'd go out next Saturday night. "I've been coming here every week for 10 years," she said. "I'm staying till they throw me out, till the bitter end."

As the queens performed their numbers, mayoral candidate Michael Brown arrived with an aide, handing out fliers deploring the "disservice to the gay community by not assisting the O Street clubs in relocating." While performers Billie Ross and Vicki Voxx (both channeling Diana Ross) did a version of "I Will Survive" (which was Gloria Gaynor -- we know, stay with us here), Brown shouted above the music that the closings are just another failure of the District "to have a plan. This never should have happened this way, and it happens to all kinds of businesses."

Past closing time, John Parks, the club's longtime manager, told people to keep partying: "Drink it so we don't have to pack it tomorrow."

Around 2:30 a.m. people mobbed the floor to hug Ella Fitzgerald goodbye and ply her with still more dollar bills. She performed "The Party's Over": "They've burst your pretty balloon," she mouthed along. "And taken the moon away/It's time to wind up the masquerade/Just make your mind up/The piper must be paid." It felt like it would go on forever.

But Monday afternoon, in the harsh light of day, Ella came back and cleaned out her things. "One more trip up those stairs," she said, "and I'm gone."